Gay Cuban history: Strawberry and Chocolate

This post is for a group I’m taking to Cuba next month! They wanted some context for the award-winning film Strawberry and Chocolate, a key piece of Cuban film history and gay Cuban history.

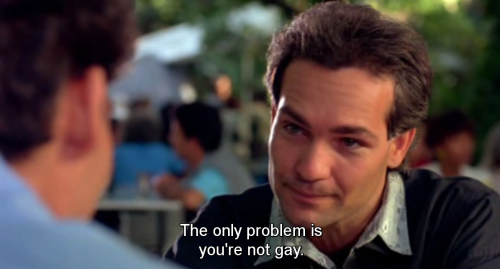

Strawberry and Chocolate is a movie that examines what it means to be Cuban. It’s basically a challenge to the Revolution’s narrow vision of what it means to be “a good Cuban” or “a good revolutionary” – and whether a gay man can be one.

Released in 1993, Strawberry and Chocolate was a huge hit. It won multiple awards nationally and internationally and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1994. The film’s release was also a watershed moment in (gay) Cuban history, sparking a national conversation about gay Cubans and their place in the larger society.

And before I go any further, a disclaimer. I know that there are more inclusive terms than “gay.” I’m using it in this case because, limited as it is, it’s the right fit for this film. Strawberry and Chocolate is about a pretty stereotypical gay man: White, middle-class, cultured, educated. So this film was not challenging assumptions about what it means to be gay, and it didn’t explore other sexual minority identities or deeper intersectionality. So sure, this is part of LGBT Cuban history, or queer Cuban history… but “gay Cuban history” is also an apt description!

Good and bad revolutionaries

Here’s the deal. The Cuban Revolution developed this concept of the New Cuban or the New Man. This was the ideal of the perfect revolutionary, patriotic as hell and “ideologically pure.” Cuba’s always been pretty black and white about this. You’re either with us or against us, a good revolutionary or a dirty traitor, etc.

Things that could make you a bad revolutionary included:

- Questioning or disagreeing with the Revolution’s political ideology;

- Committing crimes;

- Practicing any religion; or

- Being LGBT

These were all considered unacceptable kinds of deviance.

Cuba took its deviants very seriously. For a period in the 60’s and 70’s, they were rounded up and shipped off to forced labor camps for “reeducation.” And even after the camps were abolished, life was difficult. Under Cuba’s socialist system, there was no private sector. The only jobs were government jobs, and the only way to maintain a successful career was to toe the party line and maintain good standing. Depending on your workplace and superiors, a gay person might be tolerated or might be persona non grata.

Of course many people kept their politics/religion/sexual orientation secret to avoid persecution. Other deviants left Cuba and moved somewhere where they’d enjoy more political or religious freedom.

Smaller forms of deviance included exploring ideas considered un-revolutionary – including music, literature, or art that wasn’t approved by the powers that be. Revolutionary Cuba has always been paranoid about exposure to other ideas and ideologies. So for example, Cuba put all Cuban writers and artists on a pedestal, while those from elsewhere were considered suspect. Soviets were also put on a pedestal, as the U.S.S.R. was Cuba’s patron and socialist inspiration. Capitalist Western countries were presumed to be working against the Revolution, or at least at cross-purposes, especially the U.S.

Strawberry and Chocolate was set in the 80’s, when the labor camps were still relatively recent history and emigration was a leading option for LGBT people.

The complicated reality

As black and white as this all sounds, people are complicated, and so are countries. Cuba’s never been so ideologically pure as it pretended to be.

This plays out in various ways. There’s always been a lot of corruption in Cuba’s socialist system, from favoritism to bribery and theft. There’s always been a thriving black market of stolen or imported goods. Cubans have always enjoyed foreign music, even the music of “the enemy” (i.e., the U.S.). Last but not least, Cubans have always been deeply religious, even if they had to keep it quiet because the revolutionary ideal was atheism. All these practices ran counter to the official revolutionary dogma, but they were all a routine part of everyday life.

And depending largely on your positionality (generation, social class, education, race, sexual orientation, etc), personality, and intelligence, plenty of Cubans have always questioned the system – even those in good standing. They may be outspoken about it, and they may not. But many Cubans recognize deep contradictions and tensions in the system.

Characters

The film revolves around three characters: Diego, a gay man; his neighbor Nancy; and David, a young student who gets to know them.

Diego is a deviant. He’s openly gay. He listens to the wrong music and reads the wrong books. He’s collaborating with some foreign embassy to launch an unorthodox art exhibition. But at the same time, he’s a patriotic Cuban and eloquently asserts himself as such.

Nancy is his neighbor and best friend. She doesn’t seem to be very political. Like most Cubans, she’s religious. The film uses her everyday religiosity to point out the hypocrisy of marginalizing a gay man for his deviance while most of the country fails to adhere to the official ideal of atheism. A similar point is made with her illicit business buying and selling goods on the black market.

David is literally a card-carrying revolutionary. But through his association with Diego, he’s confronted with Cuba’s contradictions and challenged to think for himself. And as Diego challenges David’s assumptions and beliefs, the film challenges Cuban society as a whole.

Things to watch for

The Revolution’s leaders have always worked hard to control the Cuban people. They set up a system where “good revolutionaries” are supposed to inform on anyone engaged in suspicious activities. There’s something like a neighborhood watch across the entire country. And whether they’re informing on you or not, Cubans generally love to gossip and know what everyone is up to. You’ll see the characters thinking about the possibility of being spotted or overheard.

Nancy prays to both Catholic and Afro-Cuban figures. This is normal in Cuba. At one point, you’ll see Nancy pouring water over her body, praying, and collecting the water in a basin. This is an Afro-Cuban ritual or spell.

Diego is religious, too. He has a statue of the Virgin of Charity, Cuba’s patron saint. The Virgin of Charity is credited with saving three fishermen who were caught in a storm but miraculously survived. She’s often pictured as a lady in yellow looming over the three fishermen in their small boat, and her shrine is typically decorated with yellow flowers.

You’ll also see that when Diego serves alcohol, he pours some on the floor first for the orishas, i.e., the Afro-Cuban gods. That’s normal in Cuba.

You’ll see Nancy selling black-market goods to a neighbor.

Diego mentions a couple words in Russian: kolkhoz and mujik. A kolkhoz is a Soviet communal farm, something like a kibbutz. A mujik is a peasant.

When David is decorating, his decorations are all the most obvious symbols of the Revolution.

Then and now

This film was produced in 1993 and set in the 80’s. So it’s definitely dated. Since its release, a lot has changed. Cuba’s officially LGBT-friendly now, and this movie was a turning point in the country’s evolution. There are LGBT bars, Pride parades, and a government agency that promotes LGBT inclusion throughout society. Cuba has committed to non-discrimination and is revising the national Family Code, the laws governing families and relationships. This revision may lead to marriage equality in the next couple years.

It’s now legal to run a small, home-based business selling goods. This and other kinds of private business means that people can work and make a living outside of the government’s system, so there isn’t the same pressure to be a citizen in good standing. There’s more dissent, especially among the younger generation. Also, religion is now tolerated and doesn’t mark one as a deviant.

Some things haven’t changed. Cuba’s political dogma is still very rigid. There’s still very little room for ideological deviance. So those in official positions – including university professors, politicians, and government employees in positions of authority – need to toe the party line in order to remain in good standing. Foreign influence is still considered a threat to Cuba’s independence and ideological purity.

One other major change: The apartment where Strawberry and Chocolate was filmed became one of Cuba’s earliest private businesses, a restaurant, which is now one of Havana’s most famous. It’s named La Guarida, “The Hideout,” because in the movie this was Diego’s nickname for his apartment. The restaurant capitalized on the fame of the movie to promote itself, and there are throwbacks to the film both in the décor and the menu. When I lead groups who are interested in gay Cuban history, we always make a pilgrimage to La Guarida for dinner!

Write Your Comment